In part one of our series on understanding the Six Day War, we reviewed many of the pre-conditions and formative events that helped to catalyze the situation that Israel and its surrounding Arab neighbors found themselves in during June of 1967. In that article, we briefly reviewed the phenomena of Arab nationalism that began to break out and sweep through the Middle East, especially in Egypt during the early 1950’s. And we also critiqued Israel’s reaction to that nationalist movement, largely under Abdel Nasser, and the ensuing brinkmanship and tension that followed.

But Egypt is only one of the countries that were embroiled in war with Israel; there are also its other neighbors, namely those of Syria and Jordan. As we will see, these nations also found themselves in a period of upheaval and transition after Israeli independence, both with the resulting inflow of masses of Palestinian refugees and their own nationalist movements. And we begin with Syria.

Syria

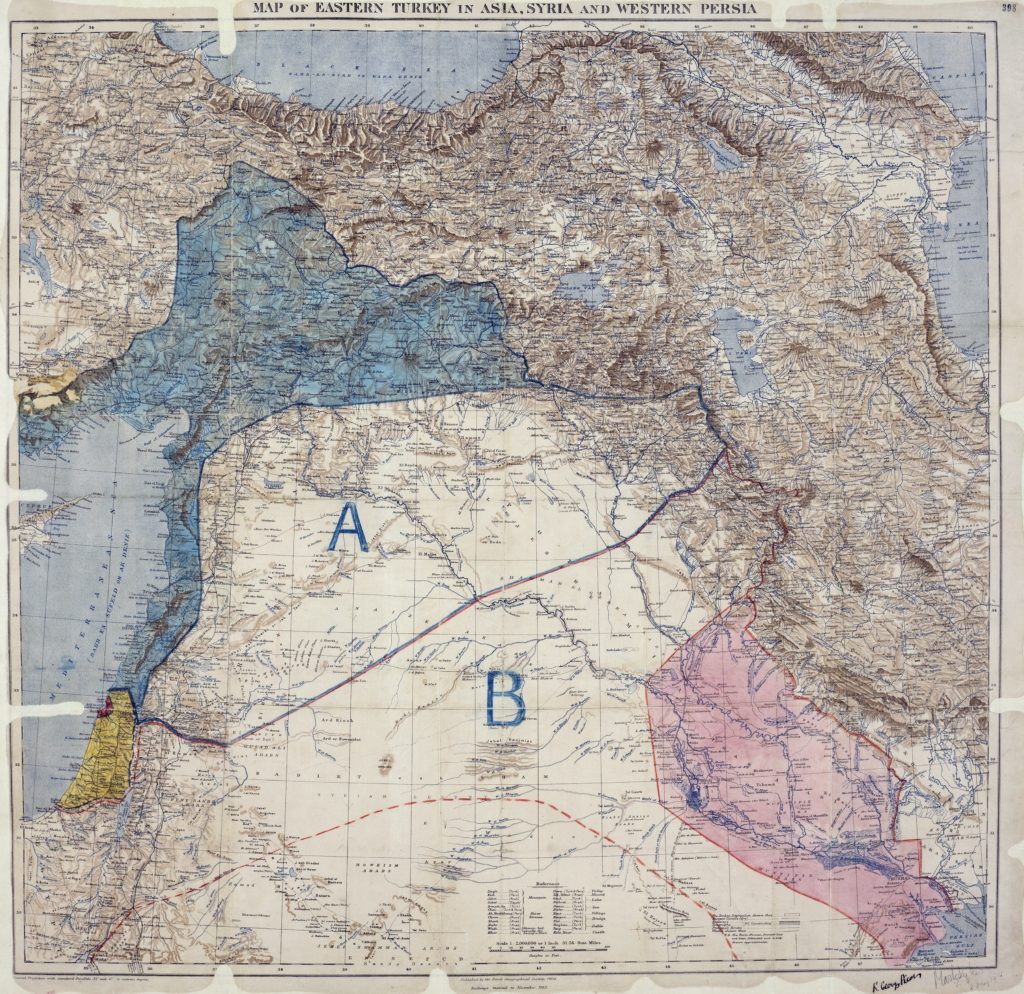

As we briefly mentioned before, the Arab nationalist movement that swept through much of the Middle East was often a reactionary movement, in a great many cases, as a reaction against past colonialism, and Syria is certainly no exception. As students of 20th century history will recall, the Sykes-Picot agreement, negotiated in secret between France and Britain in 1916, resulted in British control of much of Israel, Transjordan, Egypt, and modern-day Iraq, and French control of the northern regional states, namely Lebanon and Syria.

That influence eventually waned with Syria gaining its independence in 1945. Following on its heels shortly after the 1948 war with Israel, Syria experienced its first coup d-etat in March of 1949 beginning what would become a long period of instability, both internally and concerning Israel and its regional partners. Armistice negotiations at the time were actually still ongoing and Colonel Husni Za’im, freshly instated by the March coup, actually sought a full peace agreement, rather than a temporary armistice.

Za’im and Ben-Gurion could not ultimately agree on terms, primarily due to the prospect of ceding any won Israeli territory. An armistice was eventually reached and, since Syria had not officially possessed the territory in question, it is difficult to see Israel as uniquely at fault for rejecting Syrian terms outright. But it is the secrecy of this potential peace proposition that is alarming and set a precedent for future distrust and animosity toward Israel. Ben-Gurion did not present the peace prospect to his cabinet and, “for decades lied about the Syrians’ willingness to talk peace.” In the tragically prophetic words of James Keeley, then US ambassador to Damascus, “It should be evident that Israel’s continued insistence upon her pound of flesh and more is driving Arab states slowly (and perhaps surely) to gird their loins (politically and economically if not yet militarily) for long range struggle.” The armistice alone was eventually signed and, soon after, Za’im was dead following yet another coup, and, with him, the prospect for lasting peace.

Beginning of Conflict

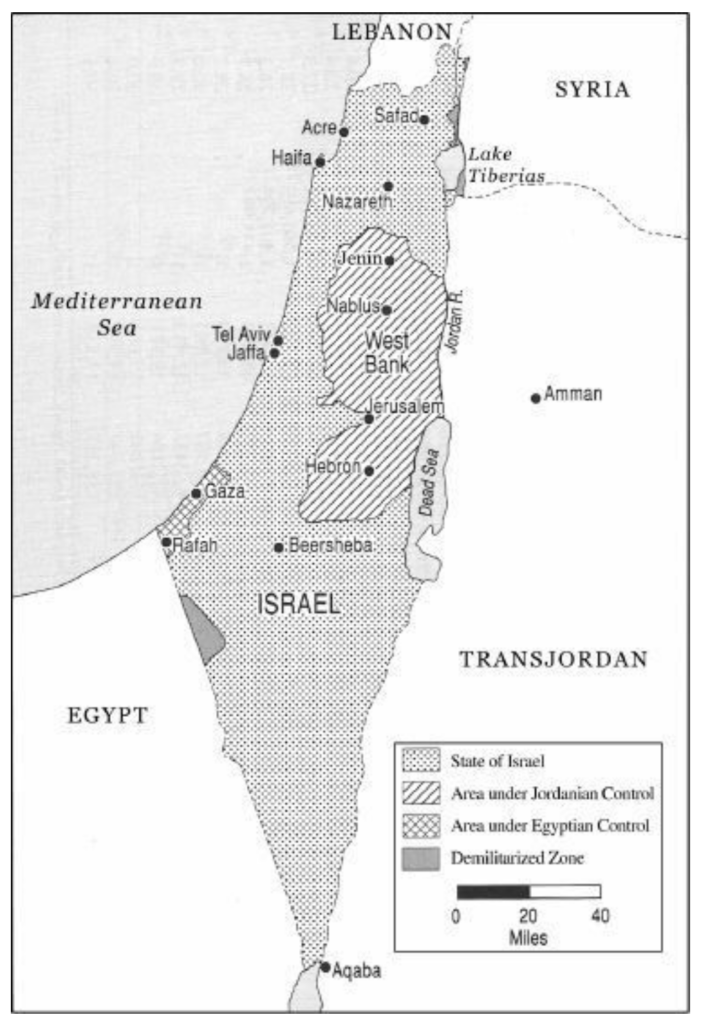

That domestic turmoil seemed to prevent conflict between Syria and Israel of the frequency and scale seen by Egypt and Jordan, at least for a number of years in the early 1950’s. Much as the bulk of conflict between Egypt and Israel existed largely along the Sinai-Negev border and the Gaza Strip, Israeli-Syrian conflict occurred along similar borders. Following the 1949 armistice agreement, those borders were established and secured within de-militarized zones, or DMZs. This land was actually rather coveted by both parties but, apart from those already living within the zones, either side was officially powerless to control them any further.

That peaceful status quo changed, however, beginning in late 1955. Moshe Dayan, then chief of staff for the Israeli Defense Force (IDF), was a central figure in the hawkish segment of Israeli politics and sought to provoke conflict between Israel’s neighbors, especially of the sort that could be seen as aggressive on the part of the surrounding Arab nations. Previously, Israeli-Syrian DMZs were rather quiet apart from some trivial Syrian provocation and trespassing. But when on December 10, 1955, Israel attempted to provoke fire by sending a police patrol near the Syrian shore of the Sea of Galilee, Syria unfortunately responded as desired. This provocation resulted in an IDF raid the next day, known as Operation Olive Leaves. The IDF overtook a series of Syrian outposts along the lake, killing a staggering 54 Syrians (6 civilians), taking 30 prisoners, and only suffering 6 of their own casualties.

And the provocation continued. During the intermediate years between 1949 and 1967, Israeli settlers were occasionally encouraged to cultivate areas within the DMZ, which Syria would be almost assured to respond to. This often involved Syrian shelling of the territory from the Golan Heights and was often pointed to as one of the threats to Israel’s very existence. And yet, despite any possible harm posed to Israeli settlers, observations by those closest to the situation routinely saw the situation on the ground in the DMZs as moving ever in Israel’s favor. Odd Bull, then Chief of Staff for UNTSO, observed that, “the situation deteriorated as the Israelis gradually took control over that part of the demilitarized zones which lay inside the former national boundaries of Palestine…as the status quo was all the time being altered by Israel in her favor.”

US consular officials also agreed with the assessment in spirit, stating in 1964 that, “Arabs concerned selves basically with preservation situation envisioned in [the UN armistice agreements] while Israel consistently sought gain full control…emerging victorious largely because UN never able oppose aggressive and armed Israeli occupation and assertion actual control over such areas, and Arab neighbors not really prepared for required fighting.” The pattern seemed to be one of provoking shelling from the Golan, which, in Finkelstein’s words, were “largely symbolic”, and then using said response as a pretext for further escalation and retaliation. And, at any rate, strictly concerning the time period directly preceding 1967, Finkelstein also notes that, “there was not one civilian casualty on Israel’s northern border due to Syrian shelling for the six-month period leading up to the June 1967 war.”

One of the key precipitating events that set the tone between Syria and Israel as well as overall Arab relations was yet another outbreak of violence just two months before in April of 1967. An Israeli tractor moving through a disputed field within the Syrian DMZ provoked a Syrian response, the result being an eventual aerial battle in which six Syrian planes were shot down.

Concerning this pattern, Moshe Dayan himself later admitted that, “I know how at least 80 percent of all of the incidents there started. In my opinion, more than 80 percent, but let’s speak about 80 percent. It would go like this: we would send a tractor to plow … in the demilitarized area, and we would know ahead of time that the Syrians would start shooting. If they did not start shooting, we would inform the tractor to progress farther, until the Syrians, in the end, would get nervous and would shoot. And then we would use guns, and later, even the air force, and that is how it went. … We thought … that we could change the lines of the cease-fire accords by military actions that were less than a war. That is, to seize some territory and hold it until the enemy despairs and gives it to us.”

Norman Finkelstein summarizes the international perspective of the conflicts quite well: “There is, however, no Security Council resolution condemning Syria for aggressive actions against Israel during this period, nor is there a veto of such a resolution. There are four Security Council resolutions condemning Israel. UN observers in the field and UN votes in New York are unanimous in holding that principal responsibility for the Syrian–Israeli border hostilities belongs to Israel.”

Palestinian Raids

Palestinian terrorism is also an oft-cited justification of the Six Day War and the support of these raids took on a different quality in the case of Syria. This Palestinian militancy began with the creation of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) along with its Fatah wing. Al-Fatah primarily operated from Syria, especially from early 1966 following a fresh Syrian coup that installed the new Ba’ath Party, actually a precursor in some respects to the modern Assad/Ba’ath regime. The Palestinian reprisals seemed to be fueled by the years of Israeli encroachment upon the DMZs as well as the continued Israeli refusal to allow refugees to return to or be compensated for their property following the 1948 war, in violation of UN Resolutions. U Thant confirms the sense that the Palestinians’ “form[ing of] their own independent guerrilla organizations to harass Israel” was in response to their “consistent refusal to comply with the recommendations of the General Assembly regarding the Palestinian refugees.”

Different from the purely state-related interests that previously existed regarding DMZ skirmishes, in the few years leading up to 1967, Syrian-backed Palestinian actions against Israel became a new focus. One of the targets of Palestinian and Syrian ire was the National Water Carrier project, a sort of canal and aqueduct that was aimed at diverting water from the Sea of Galilee to central and southern parts of Israel. The carrier was actually the target of the first military operation conducted by Fatah on January 2, 1965. The Syrian government actually embarked on their own version of water carrier project which was subsequently bombed by Israel and further escalated air war tensions.

Fatah, along with various smaller groups, “carried out some 122 raids, most of them abortive, between January 1965 and June 1967.” There is some inherent difficulty in determining exactly what sort of scale that these attacks took on due to the need and desire for a certain political messaging by both parties. Palestinian groups desired to boost their perception and numbers in order to portray a sense of success and progress and Israel often downplayed their actions in order to show a sense of success in the face of increasing hostility. As well, those raids rarely occurred from Syria, with most northern Israeli raids occurring across the Lebanese border instead, further blurring the lines of affiliation.

However, regardless of the exact numbers involved, the situation that developed in the area of the Golan is very often portrayed as one that was insufferable for Israel. Historian Michael Oren considers that, “The calculus of Syrian attacks, whether direct or through Palestinian guerrilla groups, had become overwhelming for the Israelis.”

And yet those with Israeli political and military circles as well as others close to the situation seemed to show much concrete concern. Moshe Dayan himself, in late 1966, was of the opinion that, “there is no major wave of infiltration today. Just because several dozen bandits from al-Fatah cross the border, Israel does not have to get caught up in a frenzy of escalation.” Finkelstein quotes former head of Israeli intelligence as concluding “that the ‘operational achievements’ of the Palestinian guerrillas ‘in the thirty months from its debut to the Six-Day war’ were ‘not impressive by any standard’ and certainly posed no danger to ‘Israel’s national life’. He reports that there were all of 14 Israeli casualties (4 civilians, 4 policemen and 6 soldiers) for the entire two-and-a-half-year period. Indeed, in that same time span there were more than 800 Israeli fatalities in auto accidents.”

The Bottom Line

These threats would nevertheless go on to fuel the expectation of imminent military action by both parties. Though events in Syria were a good deal less explosive and volatile than nearby Egypt or neighboring Jordan, the tense months leading up to June of 1967, Syria’s relationship with Egypt, and dangerous rhetoric from both sides, made it much the focal point. And, indeed, the perceived threat of Israeli invasion was high on the radar of Arab nations at the time, as we will soon see. But first, we must also look to Jordan to understand the state of things on Israel’s eastern border in the years preceding those momentous Six Days in June.