As we have seen in our previous two installments in this series, the build-up to the Six Day War was a slow and steady one, proceeding from a state of relative calm after the armistice agreements of 1948 and 1949, to one of eventual brinkmanship and hair-trigger sensitivity. In Egypt and Syria, Arab nationalism not only presented the native populations with a new but volatile future; it also presented a potential dangerous challenge to the newly founded state of Israel.

Neighboring Jordan, with its long, shared border and proximity to Jerusalem, experienced quite a unique history with Israel. But despite the special relationship that Jordan originally possessed, the end result remained the same.

Jordan

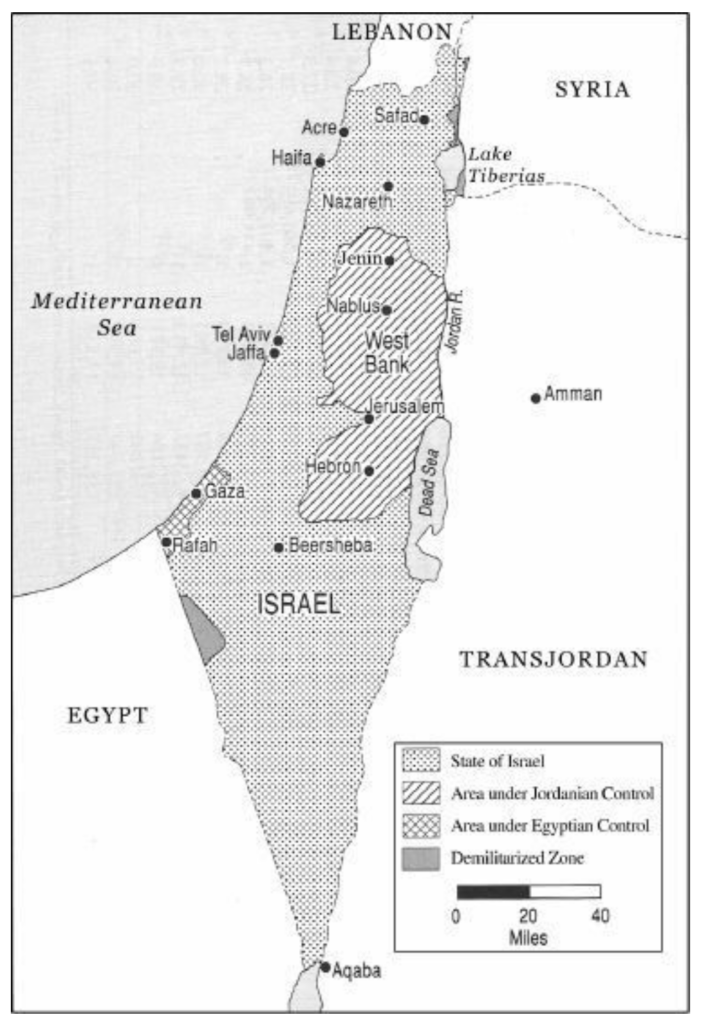

In some contrast to the Israeli border areas neighboring Lebanon, Syria, and Egypt, Jordan stands unique. The long Egyptian border along the Sinai Peninsula largely consisted of the Negev desert and less inhabited areas. But Jordan’s border after the 1948 war, containing the Jordan River and half of Jerusalem, either encompassed or abutted a large number of well-established Arab villages and cultivated land. This, of course, made it far more attractive to both Israeli settlers and Palestinian refugees during and after the Nakba.

And refugees there were. Given Jordan’s geographical and industrial advantages, it indeed found itself taking the brunt of harboring Palestinian refugees. Benny Morris breaks down the rough refugee numbers thusly: “Of the 700,000 or so refugees, about half were in Jordan, most of them in the West Bank. Another 200,000 were in the Gaza Strip; about 100,000 in Lebanon; and more than 60,000 in Syria. About half of all the refugees settled in existing towns and villages; the other half, in camps.” The huge influxes of refugee populations caused lasting, lingering issues of political and social destabilization that would, as in the case of Egypt, continue to fester and become a focal point of Israeli tension.

So it is no surprise that, as noted briefly in our prior discussion of Syria, the return of those Palestinian refugees was, at least early on, a priority for many of the Arab states. In the Summer of 1949, the Palestinian Conciliation Commission, created by the UN on December 11, 1948, held joint talks in Lausanne, Switzerland between Israeli and Arab parties. The two consistent demands at the time were the relinquishing of Arab territory taken during the 1948 war and the allowance of return of Palestinian refugees, even as few as 65,000. But both terms were rejected by Israel and no agreement could be reached. Neither the Arab countries nor Israel were interested in housing the volatile refugees that represented not only a disturbance to the economic status quo but a vast shift in political demographics.

Israel and the surrounding states went on to broker armistices individually and this task stood to be much easier with Jordan. In the decades leading up to Israeli independence, King Abdullah of Jordan had negotiated a number of under-the-table agreements with the various power centers of Zionist Jewry. He received funds from the Jewish Agency during the ‘20s and ‘30s and, as some will recall, made something of an agreement with the Palestinian Jewish powers to limit Arab Legion/Jordanian military operations during any future conflict, which eventually did occur in the Summer of 1948.

Jordan indeed emerged from the 1948 war better off in many respects and King Abdullah wished to establish a formal peace agreement with Israel in the years following. “Prime Minister Ben-Gurion and Foreign Minister Sharett, acknowledged that Abdullah sincerely sought peace,” and talks proceeded from that point, with both sides demanding some return of conquered territory and Jordan requesting some guaranteed access to the Mediterranean. Those conditions were negotiated over time at a rather leisurely pace, Ben-Gurion stating that, “I am not in a hurry, and I can wait ten years. We are under no pressure whatsoever.” As well, Israeli leadership was lax to surrender land up for concession given that, in Ben-Gurion’s words, “the land that Abdullah and other Arabs were demanding was precisely that needed for the immigrants.” But that pace eventually backfired, as much for Jordan as for Israel.

This inflow of refugees had the effect of fundamentally altering the present and future course of Jordanian polity. With Jordan’s takeover of the West Bank, Palestinians actually constituted 70 percent of its population and, unlike other refugee populations in Gaza or Syria and Lebanon, they were given Jordanian citizenship, albeit with restrictions on certain political and military membership. Over time, these new political voices became much stronger and increasingly disenchanted with peace with their Israeli neighbor. As Abdullah himself opined, “I could justify a peace by pointing to concessions made by the Jews. But without any concessions from them, I am defeated before I even start.” In epic fashion, on July 20, 1951, Abdullah was dead on the grounds of the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. Israel’s Jordanian partner for peace was gone.

Palestinian Incursion

As in the similar cases we have reviewed of Egyptian Gaza and the Syrian Golan Heights, Palestinian raids increasingly became a nuisance for Jordan as well. But Jordan represented quite a departure from the co-option and support seen in their other Arab neighbors. As noted earlier, they had taken in far more refugees than other neighboring countries and had granted those refugees far greater rights. Their unique geographical position, located along fine agricultural land with proximity to the Jordan River and nearby Jerusalem, also not only made them a target for both Israeli and Palestinian settlers but meant that many homesteads and families found their lands split or cut off after a lifetime or more of work and life.

Within these highly populated areas, much of the initial infiltration was of an innocent variety. Historian Benny Morris surmises that, “Roughly ten to fifteen thousand incidents occurred annually during 1949–54, the number falling off to six to seven thousand annually in 1955–56. During 1948–49, most of the infiltrators crossed the borders to harvest crops left behind, to plant new crops in their abandoned lands, or to retrieve goods. Many others came to resettle in their old villages or elsewhere inside Israel, or to visit relatives, or simply to get a glimpse of their abandoned homes and fields.”

Odd Bull, the UN representative who witnessed much of the ensuing conflict during the years leading up to the Six Day War, gave witness to this tragedy when he expounded that, “The main reason … was that the boundary was so drawn that the Arabs in that area were the victims of great economic hardship, since their villages were cut off from the land which for generations had been the source of their livelihood. … It is not difficult to picture the state of desperation to which they were driven when they were obliged to contemplate Israeli farmers exploiting the land which they and their forefathers had cultivated for so many hundreds of years. … It was these sorts of people who were responsible for infiltration over the demarcation line, their aim being to steal from what had not so long ago been their own land, to carry out acts of sabotage, and so on.”

As Moshe Dayan later opined, “It is not easy for an Arab government and its forces to fight infiltration. Most of the Arabs do not see theft from the foreigner as a sin at all, and as to Israel—in the wake of the War of Independence there has been added a will for revenge and feelings of enmity.… The Arab policeman has no facile answer when, coming to arrest an Arab from Qalqilya who is returning with a cow from Israel, he is asked: “What do you care if I steal a cow from Kibbutz Ramat-HaKovesh?” Nevertheless, throughout the early 1950’s, both Jordan and Egypt made formal efforts and even cooperated with Israel to curtail border infiltrations. For instance, from December 1950-February 1952, some 2,575 infiltrators were convicted and during roughly the same time period, Israel and Jordan even created “Local Commanders Agreements” meant to allow local cooperation between the states in curbing activity.

But, after the first few years, “it appears that the proportion who came armed and in groups steadily increased after 1950, largely in reaction to the IDF’s violent measures.” Those violent measures, in part, included a “free-fire policy”, adopted by the IDF early in 1948 and kept for long after. IDF troops were often given quite a free reign in violent response toward border trespassers, even given orders that their duties “at all times of day and at night will be carried out mainly by opening fire, without giving warning, on any individual or group that cannot be identified from afar by our troops as Israeli citizens and who are, at the moment they are spotted, [infiltrating] into Israeli territory.” As a gruesome example, within a six month period in 1950, Israeli troops “killed twenty-six Arabs near the line inside Israel, eleven in no-man’s-land, and twenty-three on the Jordanian side.” This is not to imply that Israel suffered no casualties or ill effects due to border incursion and conflict, only that Israel seemed to do itself no favors in its frequent, excessive reactions and policies toward any provocative Palestinian action. For reference, Morris estimates that “during 1948-56 about two hundred Israeli civilians and scores of soldiers were killed by infiltrators” while, during the same time period, “Israel’s defensive measures resulted in the death of between 2,700 and 5,000 infiltrators, mostly unarmed…”

The nature and scale of those Israeli retaliatory actions was greatly upped starting in the early ‘50s. As an example, in early 1951, Israel undertook the blowing up of two houses in the village of Sharafat in response to a murder and rape which resulted in the death of around a dozen Arab villagers, mostly women and children. Later, on October 14, 1953, in response to a grenade attack on an Israeli settlement that killed a woman and two children, the IDF sent a special command unit and paratroop company into the West Bank village of Qibya which resulted in the massacre of sixty civilians with no IDF casualties. The Qibya raid was almost universally condemned and, tragically, the Israeli government doubled down, spreading misinformation about the details of the raid while “the Israeli public was left ignorant of the facts by the heavily censored press and the government-controlled radio.”

Moshe Dayan describes the logic of the sort of collective punishment carried out against the Arab population: “The only method that proved effective, not justified or moral but effective, when Arabs plant mines on our side [is retaliation]…The method of collective punishment so far has proved effective.”

The Calm Before A Huge Storm

As it were, Jordan’s handling of more violent Palestinian infiltrations and raids into Israeli territory also stands unique. As we have seen, both Egypt and Syria eventually partnered at some level with Palestinian guerrilla groups, even to the extent of arming and orchestrating their activities. But Jordan actually spent quite a bit of effort in curtailing these raids right up until the outbreak of the war. As Bull also recalls, “the Jordanian authorities did all they possibly could to stop infiltration” with another UN observer estimating that, “Jordan’s efforts to curb infiltrators reached the total capabilities of the country.” Furthermore, Finkelstein notes that in preventing Palestinian border incursions, “more Palestinians were killed by Jordanian soldiers attempting to enter Israel than by the Israelis themselves.”

The years between the mid-1950’s and mid-1960’s appear to have represented a bit of a lull period concerning Israeli-Jordanian relations. This may have been due to the increased focus on Egypt during the build-up to, execution, and fallout of the Sinai invasion as well as increased conflict in Syria. But the establishment of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in May of 1964 represented a renewed surge of Palestinian opposition toward Israel and Jordan was not immune to its presence. In mid-1966, then King Hussein had actually attempted to eradicate much of the PLO within Amman by arresting its members and shuttering its offices, the PLO including much of the same al-Fatah group that was supported by Syria to the north.

Given Jordanian efforts to curtail Palestinian violence, it may then come as a shock that in November of 1966, Israel embarked on a massive action, including nearly 4,000 men, raiding the West Bank town of Samu. That attack resulted in the destruction of 125 homes, a school, a clinic and workshop, as well as the death of 18 Jordanian soldiers to only one Israeli soldier. The raid served as quite the galvanizing event for Jordan and those watching the situation unfold. Finkelstein notes that, “Condemning the raid at the United Nations, US Ambassador Arthur Goldberg noted that the toll it took ‘in human lives and in destruction far surpasses the cumulative total of the various acts of terrorism conducted against the frontiers of Israel’. ‘I wish to make it absolutely clear,’ he pronounced, ‘that this large-scale military action cannot be justified, explained away or excused by the incidents which preceded it and in which the Government of Jordan has not been implicated.’” E.L.M. Burns, a former chief of UN forces in the region, observed regarding Israel’s policies of reprisal, that they were “entirely inconsistent with the parties’ obligations under the General Armistice Agreements” and that the “retaliation does not end the matter; it goes on and on. … The retaliatory actions undoubtedly give some satisfaction to the Israeli public, or at least the newspapers, but the policy was not effective in relation to its professed aim.”

As well, the raid fueled further dissatisfaction between the precariously united Arab nations. Hussein fingered Egypt and Nasser in particular for failing to come to Jordan’s aid and hiding behind the then-still-present UNEF forces as an excuse. And, at any rate, it certainly appears that Amman regarded the Samu raid as a harbinger of things to come. Ilan Pappe summarizes from Israeli historian Moshe Shemesh that after the Samu raid, “the Jordanian high command was persuaded that Israel intended to occupy the West Bank by force. They were not wrong.”

The Bottom Line

With our review of the tragic fall-from-grace that Jordanian-Israeli relations experienced in the years prior to the Six Day War complete, we are finally prepared to analyze the resulting conflict itself. In the next installment of our series, we will look at the events and claims used to justify Israel’s pre-emptive war with the surrounding Arab nations and seek to understand the Israeli motivation more fully.