After quite a bit of background review around the events of the Six Day War, we are at last able to look at the six days themselves and the nature of the conflict as they unfolded. In previous posts, we looked at just how relations with Israel’s surrounding neighbors, Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, deteriorated to the state we find them in early June of 1967.

Short of a detailed military history, which is of little direct interest for our purposes, the more important concern is this: the Six Day War is used by Christians and those sympathetic to the state of Israel as a rubber stamp for future Israeli actions and an obvious example of justified pre-emptive warfare. The obvious question remains: given actions during those six days and the motivations behind them, does this characterization accurately describe the history?

The War Actually Begins

“Fly, descend upon the enemy … disperse him in the desert in all directions so that the people of Israel may live safely on their land.”

General Mordechai Hod, Commander of the Israeli Air Force

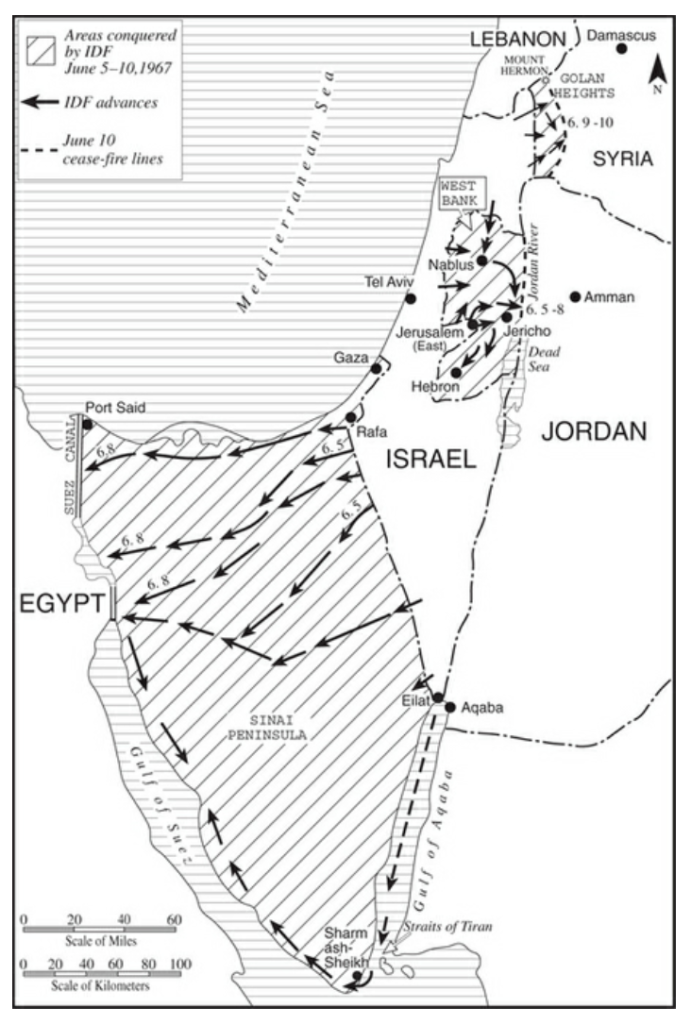

On the morning of June 5, after Egyptian dawn patrols had completed their rounds, the IAF launched what would be their surprise first offensive against Egypt in the Six Day War. This initial thrust was meant to incapacitate the Egyptian air capability and, flying from a variety of both expected and unexpected directions (even from north and west), they caught the Egyptian air forces by seemingly complete surprise. By 9:00 a.m. the results were in, with 197 aircraft and 8 radar stations destroyed or incapacitated, with the Egyptian forward operating bases in the Suez and Sinai regions effectively removed from future combat. Later that morning, an additional 100 or so Egyptian aircraft were destroyed, bringing the losses to three quarters of the entire force, and later that afternoon, Jordan’s entire air force and half of the Syrian air force was destroyed, effectively giving Israel “almost unhindered superiority over the battlefields of Sinai, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights and free[ing] the IAF for continuous support missions against the Arab ground forces.”

And that advance on Egyptian ground forces came soon after that morning, with three divisions of Israeli infantry and armor tactically crossing the border and quickly overtaking the poorly led Egyptians there. The intent was to drive them from the Sinai once again, though short of the Suez Canal for fear of increased international pressure. By June 7th, the IDF had taken the Gaza Strip as well. That same day, they captured East Jerusalem and, two days later, the West Bank.

One of the saddest trends concerning the outbreak of the war was the early insistence by some of the Israeli leadership that Israel had not actually struck first; that Israel’s actions were a defense against a preemptive Egyptian attack. Abba Eban, in an address to the UN General Assembly, held that, “on the fateful morning of 5 June, when Egyptian forces moved by air and land against Israel’s western coast and southern territory, our country’s choice was plain. The choice was to live or perish, to defend the national existence or to forfeit it for all time.” And, yet, even as of June 7, according to Finkelstein, “Israel’s London ambassador admitted…that Israel had launched a preemptive strike.” In fact, according to Churchill’s history, “the greater part of the Egyptian Air Force was caught on the ground. The only Egyptian craft airborne at the time the Israeli strike went in was a training flight of four unarmed aircraft flown by an instructor and three trainees.”

On the Syrian front in the Golan, it would seem as though the conquest of the Heights came as an afterthought. The decision to launch the offensive was not at all a unanimous and well understood one, encouraged and initiated by Moshe Dayan, without first consulting Israeli cabinet members, and the need for such an action was even more questionable. Despite the trumped up threat that Syria was said to have posed in the months leading up to the war, Ezer Weizman pondered years later that, “if indeed the Syrian enemy threatened to destroy us, why did we wait three days before we attacked it?”

On the Brink of Destruction?

One of the commonly repeated claims justifying Israel’s pre-emptive war in 1967 was that it feared for its very existence. In addition to Eban’s statements that “the choice was to live or perish, to defend the national existence or to forfeit it for all time,” Israeli documents authorizing the war claimed that, “the Government ascertained that the armies of Egypt, Syria and Jordan are deployed for immediate multi-front aggression, threatening the very existence of the state.” Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol considered “the existence of the state [to have] hung in the balance.” And Yitzhak Rabin, IDF Chief of Staff, claimed that, “It is now a question of our national survival, of to be or not to be…the noose is closing around our necks.”

There are, ultimately, a number of problems with this portrayal of Israel’s imminent destruction, some easily recognized prior to the war, others discovered or confirmed afterwards. One such problem concerns what seems to be a confused and, at times, contradictory portrayal of Israel’s war aims. Moshe Dayan, noted [commander], is noted as having informed IDF troops early on June 5, that “we have no objectives of conquest. Our goal is to frustrate the attempt of the Arab armies to conquer our country,” while two days later on June 7, he related to Israel’s leadership that those aims were to “destroy the Egyptian army and to open the Straits to Israeli shipping.” And Israeli cabinent member Yigal Allon Israel testified that Israel “sought no territorial gain.”

And yet, as we have seen previously, Nasser and Egyptian diplomats were en route and in the middle of negotations for a peaceful resolution to the blockade of the Straits of Tiran when Israel knowingly struck. As Dean Rusk, then US Secretary of State recalls, “They attacked on a Monday, knowing that on Wednesday the Egyptian vice-president would arrive in Washington to talk about re-opening the Strait of Tiran.” Israel had also broken a pledge made in late May to President Johnson not to take unilateral action for two weeks afterward. Avraham Sela testified that, “The Egyptian buildup in Sinai lacked a clear offensive plan and Nasser’s defensive instructions explicitly assumed an Israeli first strike.”

Eban also considered the Israeli resolve to go to war as dating back to “Nasser’s blockade announcement on May 22,” which predates a subsequent and imminent buildup and formation of an impending Egyptian invasion. As well, as Benny Morris relates, though Israel’s “assumption was that Egypt was intent on attacking the Negev”, “captured Egyptian documents show that Egypt’s army was in fact preparing for a defensive battle, to absorb and repel an initial IDF blow.” He also notes that, “IDF intelligence had concluded only a few weeks before, in its annual ‘national strategic assessment,’ that war was highly unlikely in the near future. A large part of the Egyptian army was tied up in a civil war in Yemen, supporting the republicans against the Saudi-backed royalists. So Egypt would probably not seek war with Israel; and without the Egyptians, the other Arab states were not likely to march.”

Despite claims to the contrary, there are also obvious indications that Israeli officials intended any such conflict to result in territorial gains. Despite Dayan’s statements to the contrary, he also declared that “Our success…will be judged not on the number of Egyptian tanks we destroy…but on the size of the territory we’ll seize.” Yigal Allon also contradicted himself in his earlier dismissal of conquest as a war aim, saying that, “In case of a new war, we must avoid the historic mistake of the War of Independence and, later, the Sinai Campaign. We must not cease fighting until we achieve…the territorial fulfillment of the Land of Israel.” These and many other similar statements express the latent desire that we have noted in previous articles regarding the lack of greater territorial gain during the 1948 war two decades earlier.

As well, Benny Morris describes Israeli concerns regarding external, UN pressure thusly: “From the first it was understood that the implementation of their [war] plan would be severely circumscribed by limitations of time imposed by the superpowers. Before June 5 Foreign Minister Eban estimated that the IDF would have no more than twenty-four to seventy-two hours at its disposal. Israel’s diplomatic missions, and particularly its delegations in Washington and at the UN, were ordered to stall for as long as possible, to allow the IDF to complete its work.” But we must ask, if diplomatic measures showed promise, why then the justification to stall? And, if indeed the threat posed by Egypt’s troop concentrations in the Sinai were truly as concrete as there were made out to be at the time, why the concern regarding UN intervention? And, yet, Abba Eban is quoted considering that “Israel has never worked harder to prevent a war than it did” at the time.

A particularly telling admission comes from Israeli Quartermaster General Mattityahu Peled. At the time, he made the claim that “the Egyptian threat had to be eliminated at once if Israel were to survive,” yet later admitted that this was a bluff.

Very Existence Threatened?

It is also a common refrain and implication that Israel held the meek position of a Jewish David encircled by an Arab Goliath, that it was an underdog or stood uniquely threatened by its neighbors. Aharon Yariv, then chief of Israeli military intelligence, remarked that “This is Egypt’s greatest hour…the combined Arab armies could push Israel back to the UN partition lines, or further…” (As though the UN partition lines were an unjust or unreasonable boundary) And Moshe Dayan was of the opinion that, “[Israel’s] one chance for winning this war is in taking the initiative and fighting according to our own designs…God help us though if they hit us first.”

And yet, this conclusion hardly holds up against Israel’s own assessments or those of third parties close to the conflict at the time. In the words of Israeli military historian Martin van Creveld, the “IDF under Rabin [was] at the peak of its preparedness…confident in its power…spoiling for a fight and willing to go to considerable lengths to provoke it.” Meir Amit, chief of Israeli Mossad, considered that, “if [Nasser] strikes first, he’s finished” and that “the war would be over in two days.” Yigal Allon had “total faith in the IDF’s ability to beat the Egyptians.” Ariel Sharon, then Divisional Commander and later Prime Minister, thought that “the army is ready as never before to repel an Egyptian attack…to wipe out the Egyptian army.” In fact, historian Norman Finkelstein considers that “the only two issues in the otherwise highly contentious literature on the June 1967 war on which a consensus seems to exist are: (a) there was no evidence at the time that Nasser intended to attack; and (b) even if he did, it was taken for granted that Israel would easily thrash him.”

And US estimates were not much different. US intelligence found that “the IDF would win a war in two weeks even if attacked on three fronts simultaneously – one week if Israel shot first.” Finkelstein relates that “the CIA estimated in late May that Israel would win a war against one or all of the Arab countries, whichever struck the first blow, in roughly a week,” the CIA chief later boasting that “we predicted almost within the day how long the war would last if it began.” President Johnson told Eban that “all our intelligence people are unanimous that if Egypt attacks, you will whip the hell out of them.” And these estimates largely considered victory in the case of defense against first strikes. The assurance of victory would presumably be even higher in the case of an Israeli first strike.

Tragically, it was partially this US confidence and “green light” that encouraged Israel to proceed as it did. Benny Morris confirms that “American intelligence accurately predicted that Israel would defeat any possible Arab coalition within a few days, perhaps a week, and by the start of June Washington had come round to the view that war was inevitable. Israel was given to understand that it could go ahead.” And though Secretary of State Dean Rusk considered the US “shocked…and angry as hell” at the Israeli initiation of war, this sentiment seemed to be split between the State Department and the President, and Meir Amit, who had spent time in Washington in the days just prior to the war, had the conviction that the US would, “bless an operation if we succeed in shattering Nasser.” It certainly did not help matters that, in the words of Finkelstein, “the United States had also committed itself to fully footing the bill for Israel’s mobilization…Israel received a green – or, in a more cautious formulation, yellow – light from the United States in early June.”

The Bottom Line

The combined weight of our consideration so far in this series has shown that the claims and mystique surrounding the Six Day War are anything but the true substance of the reality on the ground at the time. At the very least, the Arab or Palestinian powers of the day are not uniquely to blame and Israel does not represent an innocent and disinterested victim at the mercy of desert barbarism. This reality further plays itself out in the international reaction to the war and it is to that reaction we will turn in the next installment of our series.