If you’ve ever attended Sunday School in a Protestant setting within the past few decades, or regularly attended Sunday services, you’ve likely sat through a series on the book of Revelation. And, if you’re like me, and experienced this teaching with little to no theological background or previous exposure to end times teaching, you probably didn’t understand or retain much of what was taught. The book of Revelation, even for Bible teachers, can seem like a complicated thing, with many layers and components, and is easy to misread and misinterpret.

But if you did successfully remember anything from those lessons, one of the fundamental takeaways was likely what is referred to as the “millennial kingdom” of Revelation 20: the thousand-year period in which Christ and His saints will inhabit the Earth and preside in judgment over it. The nature of the millennium in Biblical eschatology has long been a matter of discussion and debate and what one believes about the timing of said millennium will dictate much of how one understands eschatology as a whole.

So it is my hope to convince you here of a truth regarding this millennium to which you will likely either viscerally reject or wholeheartedly agree:

There is no millennial kingdom. Or, rather, it’s not what your pastor told you it was.

The nature of the millennial kingdom of Revelation 20 is an important detail in any eschatological view and a proper handling of this doctrine is essential in arriving at a cohesive and systematic view of Biblical future.

First, Some Simple Definitions

But before we get too deep into doctrine, let us review some simple terminology and the relevant background being discussed.

“Millennialism,” as a suffix, serves as a description of what one believes regarding the nature of the millennial kingdom referenced mainly in Revelation 20. There are four main views found throughout Christian history and each one is intended to describe the temporal relation between the aforementioned millennium period and the second return of Christ. These four views are premillennialism (also referred to as “historic premillennialism”), Dispensational premillennialism, postmillennialism, and amillennialism.

So, for example, historic premillennialism would hold that the second coming of Christ will occur before the millennium period. Dispensational premillennialism is distinct from “historic” premillennialism mainly in its belief in the relation between the timing and extent of Christ’s return, the rapture of the church, and the purpose of the millennium period itself. While some claims of Dispensationalism will be addressed here, it is not my intent to provide a thorough review of all of its claims.

Continuing, postmillennialism holds that Christ’s return will occur after the millennium period. But amillennialism is somewhat unique. Amillennialism holds that there will be no millennium period at all, at least as distinct from the church age. Amillennialism generally views any reference to the millennial kingdom as describing the church age itself, the period of time between Christ’s death and His second coming.

Throughout church history, there has not been one particular millennial view that has historically and consistently been held. But amillennialism has certainly had its share of support by important church figures. Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, and Calvin all held to some sort of amillennial view. As such, amillennialism is held to in great measure amongst Christians within Catholic and reformed circles. But it is not enough to simply look to authority figures within church history for the basis of our doctrine. We must look to scripture itself as our guide.

How Should We Understand Revelation, Period?

It is here necessary to establish some small amount of hermeneutics and understanding of just how we ought to approach interpreting the book of Revelation as a whole. Many laypeople and certain theological schools approach Revelation in what they may propose to be a straight-forward way, viewing it as a simple description of chronological events. But upon further inspection, it can be observed that its content, while broadly appearing to flow, to some degree, chronologically, also, at times, appears to overlap. There actually seem to be seven such sections that run both parallelly and progressively: Chapters 1-3, chapters 4-7, chapters 8-11, chapters 12-14, chapters 15-16, chapters 17-19, and chapters 20-22. Not surprisingly, given this observed pattern in the text, there is a school of interpretation referred to as “progressive parallelism” that we may apply to the text to aid in our interpretation.

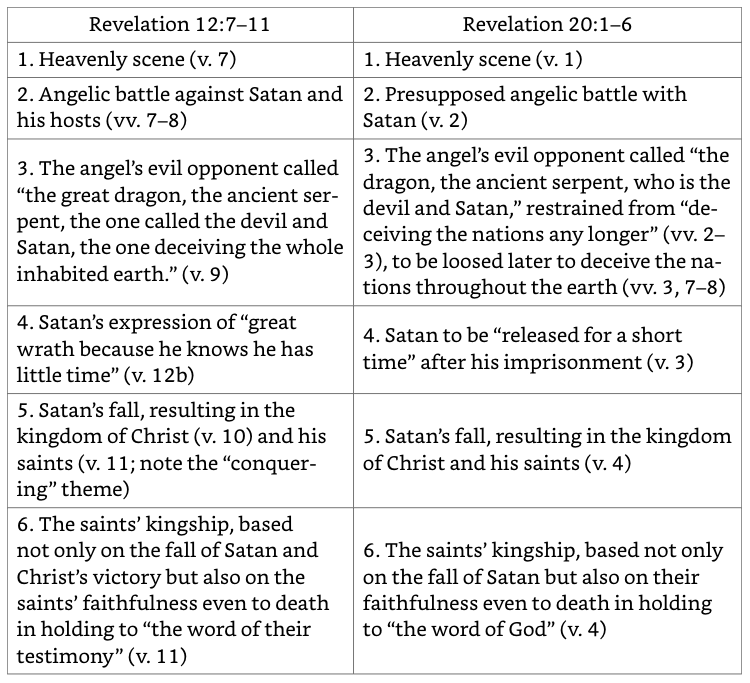

To better illustrate this concept, a quick example may be in order. One such apparent overlap exists between Revelation 12:7-11 and Revelation 20:1-6. Between these two sections, a strikingly similar series of events is described, so similar as to assume that they are actually describing the same series of events. But if indeed Revelation intends to communicate a strict chronology and does not repeat itself, this would require us to believe that these repetitive events are indeed multiple cycles of similar events rather than the more simple interpretation that they represent recapitulations of the same events told in different ways. Another illustrative example can be observed in chapters 11 and 12, where verses 15-19 from chapter 11, which describes a time of judgment and Christ’s kingdom reign, immediately transitions to chapter 12 which describes a vision of Mary in her pregnancy prior to the birth of Christ. These examples cast great doubts regarding the idea that the book of Revelation follows a strict chronology.

Additionally, we must take into account the nature of the book itself. Revelation’s apocalyptic genre, along with the fact that it is acknowledged as having been given as a vision by an angel to John directly, should make it difficult for us to approach Revelation using the same sort of “matter-of-fact” manner that we might otherwise approach other books and genres within scripture. Multiple scholars attest to this, such as Richard Bauckham, who writes, “…Revelation’s readers in the great cities of the province of Asia were constantly confronted with powerful images of the Roman vision of the world…In this context, Revelation provides a set of counter-images which impress on its readers a different vision of the world: how it looks from the heaven to which John is caught up in chapter 4.” As Alistair Donaldson concludes, “the symbolic nature of Revelation, as well as its unmistakable recapitulating structure, must be considered in one’s hermeneutical approach to the text at hand.”

On To The Text

With a proper hermeneutical framework established, we can now dissect what is left of the actual text of Revelation 20.

“20 Then I saw an angel coming down from heaven, holding in his hand the key to the bottomless pit and a great chain. 2 And he seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years, 3 and threw him into the pit, and shut it and sealed it over him, so that he might not deceive the nations any longer, until the thousand years were ended. After that he must be released for a little while.

4 Then I saw thrones, and seated on them were those to whom the authority to judge was committed. Also I saw the souls of those who had been beheaded for the testimony of Jesus and for the word of God, and those who had not worshiped the beast or its image and had not received its mark on their foreheads or their hands. They came to life and reigned with Christ for a thousand years. 5 The rest of the dead did not come to life until the thousand years were ended. This is the first resurrection. 6 Blessed and holy is the one who shares in the first resurrection! Over such the second death has no power, but they will be priests of God and of Christ, and they will reign with him for a thousand years.”

The first important observation regarding this scripture is that it is the only concrete reference to the “millennium” as a period of a thousand years. Premillennial or Dispensational scholars will be quick to claim that, though Revelation 20 alone identifies a length of time for the millennium period itself, there are other references in scripture, in the Old Testament especially. But, “as a matter of fact…”, states Anthony Hoekema, “the Old Testament says nothing about such a millennial reign.” Many of the scriptural passages claimed by premillennialists do not, in the end, reference such an intermediate period, but rather describe the final state, the new heavens and new earth, the new creation “which is the culmination of God’s redemptive work.”

Take, for example, Isaiah 65:17-25.

“17 For behold, I create new heavens and a new earth,

and the former things shall not be remembered

or come into mind.

18 But be glad and rejoice forever

in that which I create;

for behold, I create Jerusalem to be a joy, and her people to be a gladness.”

The “New Scofield Bible” actually heads verse 17 correctly as describing the “new heavens, and a new earth” but abruptly heads verse 18 as describing conditions to be found in the millennium period prior to the new creation. To be sure, the chapter goes on to describe some poetic, descriptive language that talks about exorbitantly long lifespans for infants and the elderly which would not normally, all things being equal, be expected to describe an eternal state. But, though these verses may prove challenging to interpret, this does not remove the burden of proof that is required to explain an interpretation that views here an abrupt shift in viewpoint backward in chronological time which is still far from a reliable reference to a literal, thousand year millennium. Similar passages that are often pointed to as referencing the millennium include Isaiah 11:6-10, Ezekiel 40-48, and Isaiah 2, all of which can be sensibly interpreted as describing the final state of the new creation rather than a firm reference to the millennium.

The Dispensational Need for the Millennium

What we see emerge here is a certain pattern, one that seems to desire to extrapolate a handful of verses into a bedrock eschatological doctrine. From outside of the Dispensational worldview, this pattern looks more like eisegetical reaching than a reasoned assessment of scripture. But indeed, for the Dispensationalist, the millennium does represent an indispensable necessity for their theological worldview: in the words of Ryrie himself, “the doctrine of the millennial kingdom is for the dispensationalist an integral part of his entire scheme and interpretation of many biblical passages.”

As we’ve discussed in other posts, the tenets of Dispensationalism view the church age as “parenthetical” and the millennium period represents a very unique and necessary period of time for whom they view as Biblical Israel. The millennium period is seen as the period in which all remaining prophecies made to Israel in the Old Testament must be fulfilled, without which much of the underlying framework of Dispensationalism unravels.

Naturally, the necessity of a doctrine to a particular theological school is not, in itself, a reason to doubt that doctrine or any others that relate to it. But as we have already reviewed, given the erroneous nature of how Dispensationalists view the chronology and language used within Revelation, and given the lack of solid support from the Old and New Testaments for such an understanding of the millennium, the commitment to such theological views is questionable and should at least lead us to a healthy skepticism regarding its claims.

The Bottom Line

All of this to say that we have barely scratched the surface in understanding the full extent to which amillennialism best explains the scriptural evidence for and references to the millennial kingdom rule of Christ. In part 2, we will delve deeper into parsing the language clues and apparent purpose of Revelation 20:1-6 itself and, through that exercise, discover some spiritual truths that may change the way you view the present age and the nature of the final age to come. Until then, I hope your appetite has been whetted for more and that you feel encouraged, even a little, to view study in eschatology as much less frightening and messy than you’ve experienced before.